In an era where global power has shifted eastward, a stable balance in British foreign policy requires a “tilt” to the Indo-Pacific, and as the UK goes about securing a sure footing in the region, it will find no better grounding than by deepening its defence and security relations with Japan. Japan is the only country with the right combination of geographic location, defence capability, techno-economic heft and political affinity as well as stability that fits the bill. It is time for a new Anglo-Japan alliance.

Cries of “imperial nostalgia” or “delusions of grandeur” that arise to assail this move are almost too ironic to bear. They not only miss the point that this “tilt” is about the future, they even misconstrue the lessons of the past.

One event brandished as a warning from history not to venture back East of Suez is the sinking of HMS Prince of Wales in the ill-fated Z-force that was sent to reinforce Singapore in December 1941. But if you examine this in its proper context, a completely different lesson emerges.

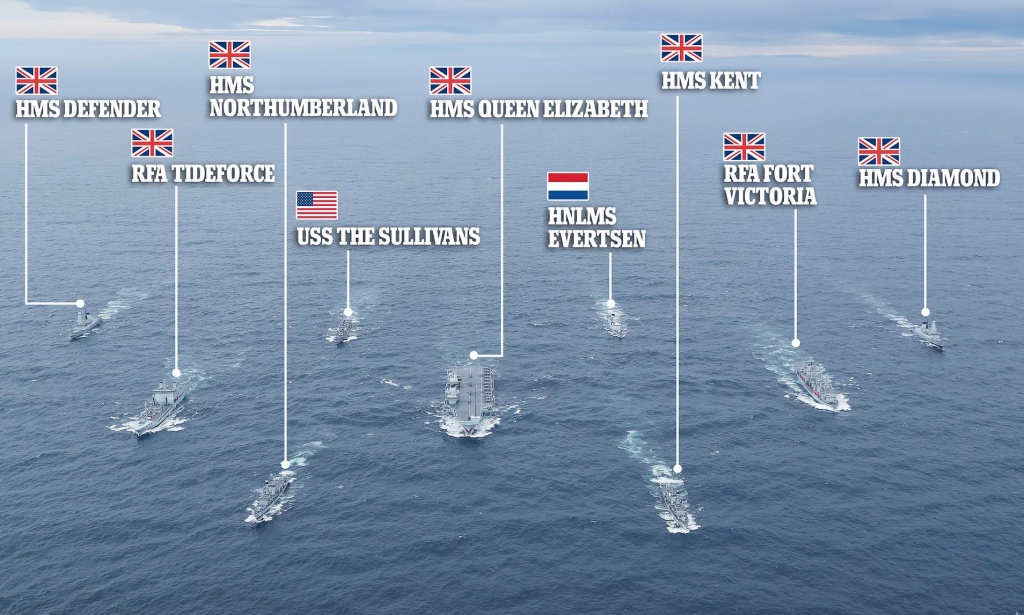

When the British Empire was near the Victorian zenith of its power, it still recognized that it could only operate in East Asia at the limits of its capability, and so decided to make an alliance with Japan in 1902 to safeguard its interests in Asia. It was only when that alliance broke up two decades later that Britain was forced to face alone the precarious situation that was to lead to its humiliating expulsion from the region. One thing often overlooked today is that the UK returned after WWII, secure once again within the framework of the US-dominated UN system of global security. There it remained to fight victoriously the Cold War in Korea, the “emergencies” and “confrontations” in Malaya and Borneo, then to see the independence of Malaya and the peaceful return of Hong Kong to China. Britain has since quietly continued to contribute to regional security through the Five Power Defence Arrangement (having its 50th anniversary this year), its logistical base in Singapore, and its presence in Brunei. So the lesson we were taught by our old friends in 1941 is not “don’t go East of Suez”, but rather “don’t go alone’. And today the British presence East of Suez is very far from alone.

But there is a second set of ironies – and lessons – to be found in the history of our first alliance with Japan, and the reasons why it ended.

The main source of tension in the 1902-22 Anglo-Japan alliance emerged from the ways Japan and Britain reacted to the rise of Chinese nationalism. While Britain was still preoccupied with fighting WWI, Japan laid down “21 demands” on China that signaled an intention to dominate not just the Chinese administration but also the interests of other powers present in China, including Britain. The irony then was that critics of the alliance in Britain thought it gave Japan a free hand, and in Japan thought it tied their hands. The irony today is that the main factor bringing British and Japanese interests into alignment is China’s attempts to dominate the region at everyone’s expense.

Another source of tension in the old alliance was British suspicion that the Indian independence movement was receiving clandestine support from elements in Japan promoting an Asian liberation movement for a mix of ideological and strategic reasons. Now the irony is the worldview of India, the UK and Japan have become increasingly closely aligned and there is consequently a rapidly developing security cooperation relationship among them under the logic of a Free and Open Indo-Pacific, and the so-called “Quad plus” arrangement.

Towards the end of the alliance, one of the nations that objected to the renewal of security ties between Japanese and British Empires was Canada. When the issue was up for consultation at the Imperial Conference in 1921, Canada made clear that it could not be placed into the position where the United States, on which it relied for its security, might go to war with its ally, Japan. Although Australia and New Zealand backed the extension of the alliance, Canada’s veto was critical. Today, Canadian warships and surveillance aircraft are operating together with other “5 eyes” allies Australia, New Zealand, the UK and America (but also with France, South Korea and Japan) in monitoring sanctions violations at sea off North Korea in an operation based out of Yokusuka, Japan.

Source: Department of National Defence, Canadian Armed Forces Combat Camera

But the biggest factor in breaking the Anglo-Japan Alliance was America. The United States had come to see Imperial Japan as its main rival and could not tolerate it having the only other global naval power (Great Britain) as its ally. As part of the negotiations to settle global affairs after WWI and against the backdrop of massive British war debt owed to America, Britain felt forced to choose between its old ally and what it hoped would be the new guarantor of world peace. Fast forward a century to 2021, the US navy is now signing trilateral agreements with the Japanese Maritime Self Defence Forces and the Royal Navy. If this is a new kind of Anglo-Japan Alliance, America seems to welcome it.

The causes for the end of our previous alliance were aspects of a single process, which was the transition – catalysed by the emerging dominance of Wilsonian America and the bottom-up rise of nationlaist movements in China and India – from a world order of empires to one of self-determining nation states. In the period that W.H. Auden called “a low dishonest decade”, and the Japanese refer to as their “dark valley”, that order was not underwritten by the commitments of its sponsors, and so proved too weak to keep the peace. The order built in 1945 was based on the same principles but charged by the mighty energies of economically, culturally and technologically dominant America and the support of its allies in the “free world”. Together their commitment and sacrifice sustained it through the turmoil of decolonization and the many challenges of communist aggression from Russia and China. But today as that order is being challenged in turn by the emergence of a large and aggressive rival, middle powers like Japan and Britain are forced to ask themselves once again ‘what is our role in this process?’ Are we bystanders or do we belong in the arena? Some historical lessons should not need to be spelled out, but perhaps this one does. If a nation with the blessings and capabilities of Britain and Japan excuse themselves as mere bystanders, the order that protects them as well as others is over.

Some argue a middle path – that the role of Britain should be calibrated to its region, and we should leave the Indo-Pacific to America. Again, history suggests that would be a dangerous course. One of the weaknesses of the Anglo-Japan treaty was that although it brought formal recognition to the interests of each party in the Asian region, it cemented a division of labour along regional lines. From the British point of view, the protection Japan gave through the alliance to its interests in Asia was welcome, but the withdrawal of British military capacity from the region that this enabled proved a destabilizing factor. By the time the alliance came to an end in the early 1920s, the dominant trend of world disarmament and arms control agreements (especially limiting ships) meant that British interests East of Malacca were to be left terribly exposed until the coup de grace in January 1942. To argue that the Europeans should “backfill’ security in their neighbourhood to allow their American allies to take care of the Indo-Pacific is to fail to learn the lesson that an alliance is sustained by shared equities, and a geographic division of labour invites a ruinous alienation.

What kind of tilt is needed, and what new type of Anglo-Japan alliance can support it? As described above, the tilt is not an uncontrolled lurch, but an adjustment of posture to secure a balance on shifting ground. Britain will always keep one foot planted firmly in its home region. But now as in the past, maintaining that strong position at home requires some shift of resources to allocate support for an alliance over the horizon, where the sun rises.

https://anglojapanalliance.com/2018/10/03/uk-assures-japan-you-will-not-have-to-fight-alone/

Public opinion in the UK is generally open to the tilt, judging by a recent survey by the British Foreign Policy Group “UK Public Opinion on Foreign Policy and Global Affairs Annual Survey – 2021”. When asked “what do you think about the notion of an ‘Indo-Pacific tilt’ in the UK’s foreign policy?” more than a third said that the UK’s involvement in the region should be balanced with investments elsewhere, since the Indo-Pacific will be important to global power dynamics and economic growth. That leaves open the question of how many of those believe we have such a balance today, or if such a balance needs more investment towards the East. Even though no policy leader is proposing it, around 8% even responded that the UK should make the Indo-Pacific “the centre of its foreign policy”. So when you sum the support for a balance that allows for the growing importance of the region with those who would go even further than current UK government policy, you find a good amount of support in favor of the tilt. Still, it must be recognized that a significant proportion of those surveyed have yet to make up their minds.

In conclusion, if we are to look to history for lessons now, perhaps these three would be among them – A world order that can deter aggression is a team effort. A geographic division of labour is an invitation to divide and rule. The few countries like the UK who are capable of operating in East Asia should, and can do so productively as part of a multilateral framework. Japan is Britain’s new ally in in that framework.